Commentators have lamented the lack of a mandatory generic prescription regime in India, with some even pointing to a perceived nexus between pharmaceutical manufacturers (“innovator” companies, to be precise) and doctors, with the former offering incentives to the latter for prescribing branded drugs.

Through a notification [MCI-211(2)/2016(Ethics)/131118] dated 21 September 2016, published in the Gazette of India on 8 October, the Medical Council of India has amended the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations 2002. The amendment is relatively short, and serves to modify Regulation 1.5, which read:

Every physician should, as far as possible, prescribe drugs with generic names and he/she shall ensure that there is a rational prescription and use of drugs.

The amended regulation reads:

Every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters and he/she shall ensure that there is a rational prescription and use of drugs.

The change effectively makes it mandatory for doctors, including those in private practice, to prescribe generic drugs rather than restricting unwary patients from opting away from brand-name drugs that are usually significantly costlier.

Lessons from the past

Administrators in the country have long believed in the benefits of generic prescription, particularly to public health institutions and insurance-backed healthcare delivery (although the latter is rare in India). Numerous approaches to mandate generic prescription in the past have largely been unsuccessful, including the MCI’s own attempt at getting doctors to comply with the erstwhile Regulation 1.5. While the amendment seems to lend some teeth to the regulation’s language, it is unclear how successful this latest push will be. It’s important to interrogate the reasons for the repeated failures of generic prescription policies in India. While drug quality has been raised as a sticking point by doctors, another grievance was that generic drugs simply weren’t as widely available on the market as their branded counterparts. One notable policy intervention in response to this claim was by the West Bengal government, which first set up Fair Price Medicine Shops at virtually all secondary and tertiary healthcare centers in the state. The WB government’s rationale was that the fair price shops would ensure a steady supply of generic drugs whose quality was reasonably assured. Following this, the WB government mandated generic prescription for all government doctors, a move that has resulted in appreciable patient benefits, according to one study. The WB programme was inspired by a similar initiative in Rajasthan, although I haven’t been able to find too much empirical data documenting its results.

The other uniquely desi problem comes from Rule 65(11A) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules 1945, which mandates that

(11-A) No person dispensing a prescription containing substances specified in Schedule H or X, may supply any other preparation, whether containing the same substances or not in lieu thereof.

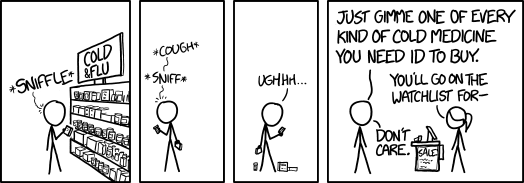

xkcd #1618: Cold Medicine

This effectively rules out the possibility of brand-generic substitution at the pharmacist level for most drugs, a practice that has found wide acceptance abroad. This means that if substitution is to take place for prescription drugs, it must be at the insistence of the prescribing physician. The US allows this to a limited extent with the Orange Book. In the UK, the Department of Health considered a radical system through which dispensing pharmacists would be obligated to automatically substitute generic drugs where available, but ended up scrapping the programme after consultations.

Prospects for nationwide implementation

Although the Prime Minister’s Jan Aushadhi Yojana currently bears the flag as far as access to medicines is concerned, it isn’t entirely problem-free. Karnataka, for example, has opted out of the PMJAY arrangement to set up its own chain of low-cost generic-focused pharmacies, pointing to the fact that the central scheme covers a narrower range of drugs. The biggest problem for the PMJAY is, as expected, quality control. Since it sources its drugs from a range of manufacturers, ensuring sustained drug quality would require rigourous sampling, testing and stringent action against offending drugs – all measures that the central government has demonstrated a tendency to shy away from.

Another controversial approach that has found some traction abroad is to incentivise doctors into prescribing generics. Essentially, this involves a dollar-for-dollar matching of the incentives that large pharmaceutical companies spend on marketing to doctors, and it’s given rise to understandable concern. However, at least one study has shown that, subject to certain constraints, sweetening generics for prescribing doctors may represent significant cost savings from enhanced generic adoption. Whether this will work in the Indian context is, of course, an open question.

In summary, we know nothing about how effective this latest push will be for wider generic prescription. There is one assured benefit arising from the amendment to the regulations: doctors will now have to write out prescriptions in block letters, meaning that you and I can finally read what we’re being asked to put in our bodies.