Image from here

This post is in continuation of my previous posts dealing with the background on the copyright infringement suit against Sci-Hub and Libgen (here) and the applicability of the fair dealing defence (here). In this post, I discuss the exemption in the Copyright Act for the purposes of education and the interim injunction plea sought by the plaintiffs.

Education Exemption

Section 52(1)(i) of the Act allows for “the reproduction of any work” “by a teacher or a pupil in the course of instruction”. This provision was the focus of attention of the landmark DU Photocopy decision. The Division Bench had interpreted it to hold that so long as any given work is necessary for the purposes of educational instruction, reproduction of such work is permissible. This essentially means that if, for instance, the plaintiff’s works are necessary for educational instruction, copies of the same can be made by students for their use. Moreover, the Division Bench also specified that the use of any intermediary or agency by the concerned student or teacher for carrying out this copying would be permissible within this provision. The caveat, however, that the court provided was the incorporation of the element of fairness under this provision. It held that this fairness has to be “determined on the touchstone of ‘extent justified by the purpose’” and that “so much of the copyrighted work can be fairly used which is necessary to effectuate the purpose of the use i.e. make the learner understand what is intended to be understood.”

Applying this rationale to the present case, the defendant websites can potentially be seen as intermediaries that provide access to works that are necessary in the course of instruction. This, however, would be a difficult argument to make for the defendants. This is because in a sense they will have to establish the necessity of each work that they have stored on their database for some instruction or the other. Moreover, it might also be contested on the grounds that under this claim the access to works should be restricted to only those for which it is necessary. For instance, it is difficult to argue why a law student necessarily requires access to scientific articles on nanotechnology.

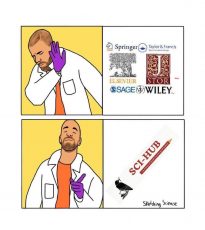

Even if this exemption is deemed to be inapplicable, another factor needs to be considered. If the court decides against the defendants in this case, that will mean that the applicability of this exception will become minimal. As Divij has explained earlier, the academic publishing industry is already skewed against access for individual researchers, students, and the scientific community at large. Furthermore, a recent piece in Scroll on this litigation aptly highlights the necessity of the defendant websites for academia to tackle the challenges posed by this exploiting structure of publishing agencies. (Also see here) This challenge is stark even for those institutions with above-average access to subscribed databases. For instance, even for writing this post, I could not access some of the authoritative commentaries on copyright law for analysis, despite having significantly higher access to resources through my University than non-institutional researchers, and the exorbitant costs to buy an individual copy. The excessive costs of subscription charged by publishing houses has led to libraries around the world highlighting their inability to afford them, including Harvard in the past. (See here, here, here, here, here, and most recently here and here) Even the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India’s largest science body, has had affordability difficulties in subscribing to major academic journals. As an aside, a detailed research on the availability of library budgets in Indian universities and the concerns on affordability of major databases within the same will be an interesting exercise. The figures for the top 3 NIRF ranked universities in Law, Medical, and Engineering share some interesting insights. For instance, the approximate expenditure on library in 2018-19 ranges from 30 lakhs to 2.4 crores in Law, 5.4 crores to 28.5 crores in Medical, and 16 crores to 19.5 crores in Engineering, in the top 3 ranked universities. These figures, however, offer a limited insight given their vast range and non-contextualised presentation as factors like receipt of external donations, extent of prior availability of resources, and segregation of expenditure on books and academic journals, significantly affects the viability of spending.

The impact of such an outcome would be exactly contrary to what the Jammu and Kashmir High Court had warned against, citing an earlier Lahore court decision, in the case of Romesh Chowdhry v. Kh. Ali Mohamad Nowsheri. The court had observed as follows:

“The Principle is now well settled that under the guise of a copyright the authors cannot ask the court to close all the doors of research and scholarship and all frontiers of human knowledge”

It is in order to prevent such an outcome that the exemptions on research and education have been provided by the Act. However, the exploitative structures of academic publishing houses coupled with the particular socio-economic conditions of India with limited access to education, internet, and other resources, make the presence of such exemptions in the Act futile. (See Swaraj’s post for more perspective on this issue)

Interim Injunction

The plaintiffs in the instant case have sought for an interim injunction to be granted taking down the defendant websites. While the court did not grant the said injunction in the previous hearing noting the lack of urgency, the short notice to the defendants and the time required for next hearing might have played a role in not granting the relief. As the IA is yet to be disposed of and this plea would mostly be raised by the plaintiffs in subsequent proceedings, the court must approach it carefully. In order for an interim injunction to be granted, three factors need to be established: prima facie case, balance of convenience, and irreparably harm. In the instant case, as I have highlighted above, there are a lot of complex issues that the court has to unpack. In this context, it would be hard to arrive at even a prima facie conclusion as to the strength of the plaintiff’s case. Even if it is assumed that the prima facie case is established, which many might think to be satisfied, the other two factors have to be independently assessed. As has been examined above, it is difficult to envision any irreparable harm to be caused to the plaintiffs if the injunction is denied, in light of their constantly rising revenues despite over a decade of the existence of the websites. Accordingly, the balance of convenience also possibly weighs against the plaintiffs, especially since the shutting down of the website would mean the prohibition on access to scientific research. Moreover, as I have examined in a previous post, while deciding upon an injunction application, the delay in approaching courts for seeking such an injunction must be treated to be inversely proportional to the possibility of success. As the plaintiffs have approached the courts after almost a decade of the existence of defendant websites, their probability of securing the interim injunction should be minimal. Therefore, the court should be wary of granting any relief until the trial is completed and the facts and law have been thoroughly examined.

Conclusion

The outcome of this litigation can be monumental for the shape that India’s research and education sector will take in times to come. In examining this critical matter, the court must keep the basic principles of copyright law in mind. As I have examined earlier, taking help of Landes and Posner’s conceptualisation of copyright as a balance between access and incentives, the public element of copyright deserves adequate attention. Presently, there do not appear to be any lack of incentives on the part of academic publishers in publishing contemporary research as can be seen from the humongous profit margins that they have. Rather, they themselves only play a facilitative role of giving voice to the research of those actually writing the concerned papers. Any concerns of incentivisation should rather focus on the authors of these works or the peer reviewers both of which play a more substantial role than the rather mechanical aspect of the publisher’s work. A downfall of this litigation going against the defendant would be the outright elimination of access to contemporary research for the numerous researchers or even students in the country. This goes against the stark purpose of copyright law to begin with. Moreover, this takes away the entire point of having academic discourse in the first place. This is because academic works will then have minimal potential in influencing modern debates on policy reforms and would turn into utopian fantasies of those sitting in institutional ivy towers. It can only be hoped that the court factors in the different considerations of a developing nation like India as against the developed nations where the defendant websites have presently been blocked, for it will have a massive impact on the research potential of the country.