Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Justice Patel has for long, been known for his delightful and insightful judgments. Earlier this month, he delivered another gem in a dispute surrounding crayons between Faber-Castell (hereinafter ‘FC’) and Cello. FC contended that Cello had infringed on its design and copyright and was attempting to pass off its crayons as FC’s.

Justice Patel has for long, been known for his delightful and insightful judgments. Earlier this month, he delivered another gem in a dispute surrounding crayons between Faber-Castell (hereinafter ‘FC’) and Cello. FC contended that Cello had infringed on its design and copyright and was attempting to pass off its crayons as FC’s.

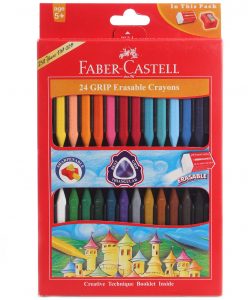

FC argued that its crayons were distinctive in 2 main ways, First, FC’s crayons have a novel and unique shape. This includes the triangular shape of the 24 crayons in the packet as well as the twin series of parallel lines of dots on the three shanks of each of the crayons. Secondly, the manner of presentation of the crayons is also unique. They are in two recessed trays facing each other within a larger outer container. Justice Patel describes this as thus: “when placed like thus, these crayons look nothing so much as vibrantly coloured missiles in antipodal silos: one battery of these crayon missiles faces the other across the demilitarized zone of shallower recesses (ditches, in our martial analogy) that hold, predictably, a benign eraser and a useful sharpener.” Therefore, there are five key and distinctive elements to FC’s crayons: their triangular shape, that they are sharpenable, that they are erasable, their non-slip grip and their arrangement in the tray. While FC does not claim a monopoly with respect to any one of these elements, they contend that the “combination of all these facets in this particular manner and presentation goes beyond the merely functional. It is entirely aesthetic and novel, and certainly unique to Faber-Castell and no one else.” Thus, it is submitted that the aggregate of all these elements is “entirely capricious”. FC then submits that Cello’s crayons bear an unholy resemblance to FC’s crayons and that this was a wholesale passing off of Cello’s crayons as FC’s.

Cello, on the other hand charged FC with suppression. It argues that such suppression is material particularly as the key elements of FC’s crayons were purely functional and not capricious additions. Therefore, Cello argues that if there had been prior publication of FC’s designs, then the burden on FC would be significantly higher. FC would not only be unable to argue design infringement at the interim stage but they would also have to show that the features of their product are neither purely descriptive nor purely functional, that there is exclusivity attached to those features and that confusion is inevitable or has actually occurred.

Justice Patel first considered the issue of capriciousness. His analysis of the same in paragraph 12 of the judgment is worth reproducing in whole: “A word first, about this term ‘capricious’, one that I have used three times already. It is, as I understand, a term of art in the field. It is today carried forward from the judgments of several decades ago, and I believe it was first used in a stricter and more formal, even antiquarian, sense than we are wont to do today. It meant then ‘fanciful’ or ‘witty’, a usage now obsolete. Today, it connotes a conduct or act that follows no predictable pattern, determined or marked by whim rather than reason. Its many synonyms show our understanding to be of significant negative implications: arbitrariness, whimsy, unevenness in dealing, unpredictability, impulsiveness, fickleness, erraticism; being volatile, unstable, temperamental. In the context of design law, it means none of these things. It does not mean frivolous, flippant or facetious. It means, at least in my comprehension of it, simply something that is not purely functional; a triumph of form over function, perhaps. It speaks to the existence of an aesthetic or artistic appeal in a design as opposed to one that serves only a functional purpose.” (emphasis added)

In this context, he examined whether the key features of FC’s crayons were capricious or not. He noted that the twin series of parallel lines of dots as well as the name and logo of FC embossed on the crayons are artistic and not functional elements. He also noted that there was nothing to suggest that the twin parallel lines of dots provide the functionality of a better grip or that such parallel lines of a specific length aid any such functionality. He stated that if at all the twin parallel lines were functional, there was no reason why Cello had chosen to not extend them across the entire length of the shanks and had instead chosen to stop at the exact length FC had stopped. Therefore, he ruled in favour of FC on the issue of capriciousness.

He then considered the various authorities on passing off. He first examined the case of Jones v. Hallworth, which considered the issue of whether permissible copying of various features might result in impermissible passing off of the whole. The High Court in Jones stated: “No one contends that the Defendants are not entitled to manufacture and sell polishing cloths; nobody contends that they are not entitled to manufacture and sell polishing cloths of certain sizes, or to impress thereon by printing or otherwise certain words; nobody contends that they are not at liberty to make these of Egyptian or American cotton, and, if they make them of Egyptian cotton alone, or of Egyptian and American cotton mixed, not to produce them of a certain colour. Nobody contends that this fact pile velveteen is not open and common to the trade and suitable to the particular article; that it may not be singed; that it may not be scoured. All those things are perfectly common to the trade; every one of them may be done with perfect innocence. But, by an inductive process, one may come to this conclusion, that every one of those perfectly innocent things when combined in a series may produce something which is the reverse of innocent.”

This is exactly the position in the instant case. On comparing the products of both parties, it was observed that the only distinction between the two was that FC’s name and logo were missing on one of the shanks of Cello’s crayons. All the other features of Cello’s crayons were exactly that of FC’s. Therefore, taken together in aggregate, the Bombay High Court held that such a combination of features including the exact length of the parallel lines of dots and the same manner of presentation as FC’s crayons indicate passing off.

Justice Patel then went on to examine the Whirlpool case which considered the issue of where a particular element has both form and function. The Bombay High Court in that case held that the mere existence of function combined with form did not disentitle such an element from protection altogether. However, in that case, the external shape of the washing machines was held to have no functional purpose. In such a situation, it cannot be argued that the functionality of the elements were such that it was not possible to have any alternate design other than the Plaintiff’s design. Moreover, when the external shape of the washing machine has no functional purpose, it is redundant for the Defendant to employ a defense attributing features of the Plaintiff’s design to functional requirements. Applying the same principles to the instant case, as Cello has been unsuccessful in showing functional uses for the key elements of FC’s crayons, it could not argue that this was the only possible design it could have employed.

After considering the other authorities in this area, Justice Patel held that from the view point of the target audience of a child or a harried parent, there was no distinction between the two products. He stated, “that every single feature that is being used in a unique fashion by Faber-Castell in creating their products has been replicated, as Mr. Dhond put it, down to the last millimetre, in Cello’s product. This is an exact fit with the Jones v Hallworth, Whirlpool and Pikpen tests. Indeed, other than the embossing of the Faber-Castell name and logo on one face of the triangular crayon, I do not see how at a visual glance anyone would be able to tell one product from the other. To adopt one feature may be happenstance; two might be coincidence; to replicate them all, Mr. Dhond insists, and I think with some considerable justification, is, if not actually enemy action, certainly deserving of an injunction.” (emphasis added).

Thus, the Court granted an injunction in favour of FC, noting that the longer Cello’s crayons remained in the market, the greater the continuing loss to FC would be.In order to view comparative images of both the products, please refer to the judgment available here.

At a time when we are ruing the quality of judgments from the Delhi High Court, the Bombay High Court and particularly Justice Patel’s Court do much to raise our spirits and our faith about the future of IP in our country. It is therefore entirely unsurprising to us that Justice Patel is included in Managing IP’s 50 Most Influential People in IP along with Justice Prabha Sridevan and our very own, Professor Shamnad Basheer, This judgment along with the other well-reasoned and well-written judgments that have flown from Justice Patel’s pen shine as a beacon in our IP jurisprudence.