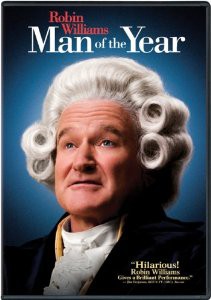

Clik here to view.

Unfortunately, of no relation to this movie

I’m very happy to bring you a guest post by a dear friend of the blog, Mr Zakir Thomas, on the entrepreneur who ironically may have managed to bring more scrutiny on the out-of-control circus that drug pricing is, than health activists have managed in years of trying! Yes, we’re talking about the infamous Martin Shkreli. Readers may remember that I had voiced a similar sentiment in my piece titled ‘The Good that Martin Shkreli has done“. In this piece, Zakir Thomas takes up more examples and further exposes the lack of a rational basis to the pricing of pharmaceutical prices by Big Pharma. Zakir Thomas was a founding project director of CSIR’s Open Source Drug Discovery program and also former Copyright Registrar of India. Readers may also be interested in this interview of his that we’ve hosted earlier.

Title: Martin Shkreli: The Man of the (Pharma) Year 2015

Author: Zakir Thomas

Martin Shkreli is reported to be the ‘most hated man in America’. He has been called ‘morally bankrupt sociopath’, ‘scumbag’, ‘garbage monster’ and many harsher monikers. A Google image search reveals much more.

Yet, I think he is the Man of the (Pharma) Year 2015.

His claim to (in)fame started with his company Turing Pharmaceuticals acquiring the rights to produce Daraprim, a generic drug developed in 1950s and used by AIDS patients. The chemical name of the drug is pyrimethamine. Till Martin Shkreli appeared in the picture, the drug cost about $13.50 a dose. Turing Pharmaceuticals was the only approved manufacturer of pyrimethamine. The absence of other generic drug manufacturers gave him an exclusivity in the market. Shkreli raised the price to $750 a pill, a 5,000% increase. This decision, criticized widely, earned all the sobriquets mentioned above.

Shkreli claimed that he was simply following the principles of the system. He did what any other entrepreneur in the capitalist society is supposed to do – maximize profits for the shareholders to whom he is responsible. Drug prices are inelastic. Shkreli believes that his duty is towards his shareholders to ensure them returns. He could ensure it only if he keep the price at the top of the curve. He even regretted later that he did not raise the price higher.

This begs an alternate question: is there a rational basis for pricing of pharmaceutical products marketed by big pharma?

The pharmaceutical pricing policies are one of the biggest mysteries of the corporate world. But pharma industry claims a rationale – the high prices are necessary to meet the huge R&D expenses for developing a drug. What that expense is, is yet another mystery. Currently it is estimated to be $ 2.6 billion per drug. Two years back when the estimate was $ 1 Billion, GlaxoSmithKline’s chief had described the figure as a myth.

The Economist recently opined that the drug development costs estimated by various studies are irrelevant and inapplicable now as the industry is moving towards a new model. The industry has moved away from the model of spending heavily on different areas of cutting edge research and the large pharma firms are buying in drugs that are already in the course of development. In some cases, they do so by buying other firms having promising drugs. The Economist cited a few examples. Pfizer acquired Lipitor, its blockbuster cholesterol lowering pill by acquiring Warner Lambert. Likewise, Gilead’s bestseller Sovaldi was acquired through takeover of Pharmasset. Merck’s purchase of Idenix is reported to acquire its competing drug to Sovaldi. The Economist referred to a study by Bain, a consulting firm, which concluded that 70% of the pharma sales are from products developed elsewhere and not out of internal R&D.

Another drug recently in news due to high price is Xtandi, sold by Astellas Pharma. It has an average wholesale price in the US of more than $129,000. This prostate cancer drug was invented at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) on NIH and Department of Defense grants. Astellas’ response summed up the pharma approach to drug prices. They believe that drug price to reflect the innovation and patient benefit provided.

Pharmaceutical companies have moved to a model of making incremental changes to their existing drugs with small advantages out of limited R&D but big price differentials over rival treatments.

Let’s take the example of Sovaldi, a Hepatitis C treatment marketed by Gilead Pharma. It has been in news globally after its launch in 2014. The 12-week course of treatment in the US was $84,000 ($1,000 a pill). What is the basis of this pricing? Gilead gives the pharma rationale of high R&D cost.

How does one assess the basis of pharma pricing? Gilead did not develop Sovaldi in its laboratories. It was a drug developed by Pharmasset. According to The Economist, Pharmasset had planned to price the drug between US$ 36,000-72,000 for a course of treatment. But Gilead put the drug in the market at $84,000. What is the rationale? The only one that can be thought of is that, there is no rationale. At least the price has no relevance to the R&D cost, as Pharmasset who did the R&D in house was planning to price it less.

The Gilead example show that a drug’s new owner pricing it more than the previous owner is not new in pharma industry. Martin Shkreli says the previous owners of Daraprim underpriced the drug and so he increased it. If this practice is followed in pharma industry and we do not complain, why blame Shkreli alone? Is Shkreli the only pharma boss who has done it for you to hate him?

Gilead is hailed for bringing Sovaldi to the market, and Shkreli is portrayed as a villain for following a similar approach in the pharmaceutical industry. Shkreli thinks that the (US) market can afford his price. He followed the current pharma logic that the price of a drug is the value it commands in the market.

Shkreli, like other successful entrepreneurs did not stop with one drug, Daraprim.

He led a team to acquire and got appointed CEO of KaloBios which announced its plan to purchase the rights to the drug, Benznidazole, from Savant Neglected Diseases LLC for an upfront payment of $2 million (plus milestone payments). Benznidazole, developed in 1970’s is one of only two drugs used to treat Chagas Disease– the other is called nifurtimox and has serious side effects. Benznidazole is on the Essential Medicines List of the World Health Organization (WHO) but has still not been approved by FDA for use in US. Industry has not approached FDA for approval probably because the number of Chagas patients in US is limited. It is estimated that getting an FDA approval for a generic drug costs about $ 400,000. Currently the drug is available free of cost for patients in US from Center for Disease Control.

He announced that, upon approval he will price that drug at levels similar to Hepatitis C drugs. Benznidazole, currently available free would cost anywhere from $63,000 to $95,000, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The real rationale for this acquisition is more insidious. By acquiring the rights to produce Benznidazole, Shkreli would, apart from higher profits, also benefit by getting what are called the Priority Review Voucher (PRV) of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), upon approval of the drug for Chagas Disease. PRV’s are given to those who develop drugs for Orphan Diseases and Chagas Disease is classified as one. These vouchers can be further traded. Shkreli plans to do that.

And why not? There is a lucrative market for PRVs. PRVs command upward of $ 350 million. Does it not make sense for Shkreli to acquire a company for $2 million, get a PRV which can be traded for $ 350 million, thus maximising returns to shareholders? There has been an understandable uproar from civil society. But, Shkreli has only followed a practice in the industry. Industry majors buy these vouchers. If they can buy, can’t Shkreli sell?

Shkreli says profits will be used for R&D on new drugs. This is the claim which the entire pharma industry always makes. Acquiring a company to acquire rights to a drug which can return a profit is a pharmaceutical industry practice. Creating value for shareholders is what pharma industry does. So, essentially, Shkreli followed the rules of the pharma game.

Shkreli just did what pharma does! He was just been forthright in his communication. He did not sugarcoat the price and the approach to maximize profit with the suaveness of the pharma executive. We find it difficult to digest this logic when it was conveyed to us in straightforward manner by Shkreli. The logic remains unchanged, however it is communicated. The logic which we have unconsciously accepted but when someone like Shkreli tells us upfront, we cringed.

Martin Shkreli just did something similar to the boy who shouted “the king is naked’’. Only, he went one step further. He not only shouted that the (pharma) king is naked; he went on to remove his own cloths. If the king can walk naked, so can others!

In my view Shkreli has pointed to us our own double standards. We hail pharma industry as heroes for their continuous act of doing what Shkreli did, though he did it in a slightly less sophisticated manner. When Shkreli did the same thing, and talked to us in a language we understand, we called him names.

For opening our eyes to this fact, for letting us know of our own duplicity, he deserves to be hailed Man of the Pharma Year 2015.

Tailpiece: Martin Shkreli was arrested on securities fraud charges in December 2015. The arrest and the fraud charge is not discussed here. Subsequent to the arrest Shkreli resigned as CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals and was removed as CEO of KaloBios. The issue that he raised regarding the pharmaceutical prices is relevant and shall continue to be of relevance whether he is in business or not.