Inika Charles, our Spicy IP Fellowship applicant brings us this interesting tidbit on Whatspp’s new end to end encryption. This is her fourth submission for the fellowship.

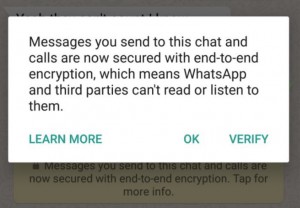

In wake of the Apple v. FBI controversy, WhatsApp has announced that all messages, photographs, videos, files and calls sent and received on WhatsApp software released after March 31, 2016 will be encrypted end-to-end. What this essentially entails is that, by a default setting, only the people sending or receiving the messages will have access to them. They will not be stored in plain text on WhatsApp servers, and WhatsApp will not hold the encryption keys to access the messages. Thus rendering them unable to comply with court orders for their decryption. The rationale behind this move was explained on their blog:

“The idea is simple: when you send a message, the only person who can read it is the person or group chat that you send that message to. No one can see inside that message. Not cyber criminals. Not hackers. Not oppressive regimes. Not even us.”

They further released a white paper technical overview detailing the signal protocol used by WhatsApp (access it here). Interestingly, the signal protocol is an open source software, developed by Whisper Systems, and has been in the pipeline since 2014. A few points to be kept in mind, are that this encryption would only work on apps running the latest software, and that only the content of the messages sent will be encrypted – WhatsApp still reserves the right to store mobile numbers involved in conversations. Most importantly however, echoing the Apple debate, this move will be seen as a blow to national security, with Governments effectively losing the ability to track any sort of communication on WhatsApp.

In the India, encryption is not per se regulated. Although Internet Service Providers are permitted the use of encryption to some extent, applications such as WhatsApp, Skype and Viber do not qualify as either telecom, or internet service providers. These applications that use internet to transmit messages or voice calls are known as “Over-The-Top” services, or OTT’s. TRAI issued an OTT Consultation Paper in 2015, which confirms that these services are not yet regulated, but they are yet to issue regulations on the matter.

As far as interception of messages goes, the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 provides for the interception of messages in the event of public emergencies or for public safety. Section 69 of the IT Act enables the Government to order the decryption of information in the additional, and admittedly wide provisions for the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence. Additionally Section 84A introduced by the 2008 Amendment to the IT Act, gives the Central Government the power to prescribe the mode or method of encryption. These provisions make clear that should action be initiated against WhatsApp in an Indian Court, it would not be without legal backing.

Readers might recall the BBM controversy, which culminated in Research in Motion (RIM) allowing the Indian Government access to previously encrypted messages, through a ‘lawful interception system’. Such intervention would be made impossible, unless WhatsApp is pressurized into creating back-door access to their user information. However, this would defeat the purpose of their software, and go against their clear stand on protecting the privacy of their users. Should this go to court – the balance between the right to privacy, and the threat of national security will be the major bone of contention.

While this move by WhatsApp is a huge win for user privacy, law enforcement agencies are sure to react badly. The already existing stand-off between tech companies and law enforcement was perhaps, just made harder to resolve. With Apple, the dispute centred around the ability to unlock an iPhone at will. With WhatsApp however, law enforcement faces inaccessible communication between more than a billion phones of different makes, a hurdle exponentially more difficult to cross.

Image from here