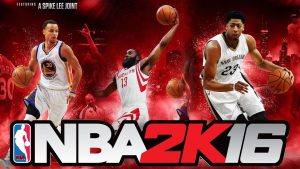

In January this year, the creators of wildly popular NBA 2k16 videogame were dragged to court by Solid Oak Sketches – the exclusive owner and licensor of the copyright to tattoos on the bodies of NBA players like LeBron James and Kobe Bryant, both of whom, together with their famous inks (see here and here), feature in the videogame. Solid Oak claimed that in making unauthorized digital reproductions of the tattoos on the bodies of the players, the creators had infringed their copyrighted works.

In January this year, the creators of wildly popular NBA 2k16 videogame were dragged to court by Solid Oak Sketches – the exclusive owner and licensor of the copyright to tattoos on the bodies of NBA players like LeBron James and Kobe Bryant, both of whom, together with their famous inks (see here and here), feature in the videogame. Solid Oak claimed that in making unauthorized digital reproductions of the tattoos on the bodies of the players, the creators had infringed their copyrighted works.

This however, wasn’t the first time that a lawsuit for infringement of copyright in body ink had been filed – the world had already been taken by surprise back in 2011 when world heavyweight legend Mike Tyson’s tattoo artist sued the Warner Bros for recreating Tyson’s face tattoo on Ed Helm’s character in Hangover II. But because the few cases centering around the issue that have cropped up in the recent past have by and large been ultimately settled out of court, there is little available jurisprudence rely on as far as the copyrightability of tattoos is concerned.

A primary examination of the issue reveals that the yardstick used to ascertain whether tattoos are in fact copyrightable is the same as that of all the protected works covered by the Copyright Act – by virtue of falling in the ambit of an artistic work, tattoos must necessarily fulfill the originality standard by proving both creativity and independent creation, and must be fixed in a tangible medium. To ascertain whether tattoo art can actually do that, it is necessary to briefly examine how tattoo designs are made.

While some enthusiastic recipients come up with their own ingenious designs, in other cases artists use pre-designed flash art images shared freely within the industry, borrow from somebody else’ previous works, or create custom designs. In all the above instances excluding custom works (being copyrightable) and flash art (being in the public domain and intrinsically ineligible for protection), the designs are essentially derivative works, and cannot be copyrighted.

As far as custom works are concerned, it would seem overly obvious that by virtue of being the artists’ creations, and as in most cases, exclusively owned by the artist, the copyright in tattoo designs by themselves should be considered no different from ownership rights in other artistic works. However, what sets tattoos apart from other ordinary artistic works is that this particular work of art uses the human body as a canvas – necessitating an investigation into whether the human body can actually be considered a legally admissible medium of expression.

To be copyrightable, an ‘original’ tattoo design must also be fixed in a tangible medium of expression. The ten thousand dollar question is whether the human body is in fact a ‘tangible’ medium of expression.

Nimmer certainly thinks not. In a suit filed by the artist that inked Mike Tyson’s Maori ‘tribal’ face tattoo (Whitmill v. Warner Bros. Entm’t, Inc) the renowed US copyright law pundit offered to testify in this case on this very issue. Likening tattoos on a human body with frost on a windowpane, he asserted that live bodies do not qualify as a medium of expression, and thus, deemed copyright protection for tattoos an unprecedented development.

Nimmer certainly thinks not. In a suit filed by the artist that inked Mike Tyson’s Maori ‘tribal’ face tattoo (Whitmill v. Warner Bros. Entm’t, Inc) the renowed US copyright law pundit offered to testify in this case on this very issue. Likening tattoos on a human body with frost on a windowpane, he asserted that live bodies do not qualify as a medium of expression, and thus, deemed copyright protection for tattoos an unprecedented development.

I initially had some trouble reconciling myself with that assertion, because what we’re talking about here are not temporary tattoos, but permanently fixed (and not transitory) body art that essentially ought to be looked upon as fixed in a ‘tangible’ medium. However, upon examining 17 U.S. Code § 101, things seem to fall a bit more into perspective and the essence of Nimmer’s assertion as to the non-copyrightability of tattoos becomes clearer.

Nimmer claims that the human body is a “useful article” – a phrase that goes without mention in the Indian Copyright Act, but is defined under the section as “an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. An article that is normally a part of a useful article is considered a “useful article”. It further states that “the design of a useful article, as defined in this section, shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article” – thus raising the complex question as to whether the tattoo can be separated from the body upon which it is drawn, and by thus independently existing be capable of copyright protection without inhibiting the rights of the recipient himself.

In my next post, I further explore this very question.